- Home

- Sujatha Fernandes

Close to the Edge Page 4

Close to the Edge Read online

Page 4

As an aspiring emcee, I had heard that Cuban hip hop was the site of a rebirth of revolutionary rap music. All kinds of American rappers, from the indie star Common to the rapper-turned-actor Mos Def, had come down here to perform at the annual hip hop festival. In her emails from Havana, Deepa described in detail all the rappers and producers she was meeting and told me she could introduce me to them. I was intrigued. What did hip hop look like in this place where revolution had such a potent meaning and history? Hip hop was known as a revolutionary music, as a culture of protest, but what would hip hop be in a country like Cuba, where the state itself was said to be revolutionary? Could it be a counter revolutionary force here?

Cuba seemed the ideal place to continue my journey in search of a global hip hop generation. My exploration had begun in Sydney, where I joined in workshops for a hip hop theatrical production on Sydney’s West Side. But as I watched hip hop in Sydney being taken over by mainstream record labels, I wondered if I might find a purer, more authentic, form of the culture in Cuba. What would it be like in a place that had not been infiltrated by Americanization? I was curious about how a digital age music like hip hop had developed such deep roots in a metropolitan city that had only two Internet cafes. What could it tell us about the power of hip hop as a truly global form?

There’s no time to sleep,” said Deepa, as she climbed into the back of the powder blue 1952 Chevrolet. “We’ve only got an hour to drop off your bags and make it to the rumba.”

Our driver sped along Boyeros, the long road from the airport to the city, and headed for the tree-lined suburb of El Vedado. Deepa helped me lug my bags up the flight of stairs to the casa particular, a private home where she was renting a room from a Cuban couple with a teenage daughter. My sleep-deprived body longed for the bed with its fresh sheets. Outside the driver beeped his horn impatiently.

“C’mon,” prodded Deepa, sensing I was weakening. “There’ll be plenty of time for sleep later.”

The National Writers and Artists Union, known locally by its acronym, UNEAC, was at the corner of Calle 17 and H in El Vedado. There was a rumba on its lawns every Wednesday afternoon. At the gates of the mansion that housed UNEAC, a young man sat collecting money.

“Don’t say anything, just follow me,” Deepa instructed, as we approached the front of the line. She handed him a ten-peso note and he let us in.

“What was that about?” I asked her, once we were inside the gates.

“Cubans pay in pesos, foreigners pay in dollars.” She indicated a blond woman at the gate, who was fishing out a five-dollar bill.

Cuba faced a severe crisis after the collapse of its main bene-factor, the Soviet Union, in 1991. Anticipating internal unrest in Cuba, the US had tightened the screws of its three-decade economic embargo, making life even more difficult on the island. The Cuban government christened these years the “Special Period.” The dual peso-dollar economy had developed in the early nineties as a strategy to help the economy recover. After years of being seen as contraband, the dollar was now recognized as legal tender. Dollars entered through remittances from Florida, tourists on vacation, and money earned abroad. But Cubans still earned in pesos. With an exchange rate of twenty-one pesos to the dollar, we had paid just twenty-five cents each to get in. That was the same as Cubans would pay. Deepa was being paid in pesos by Radio Habana, so she was entitled to the peso rate. But she didn’t even need to produce ID. No one here suspected we were foreigners. This was one of the perks of looking Cuban.

There were a hundred or so people gathered on the lawns of UNEAC. Foreigners and Cubans, kids and their parents, and older people resting in the shade all waited for the show to begin. Salsa came from speakers on the stage. A few well-dressed young Cuban men mingled with the French and Scandinavian tourists. The Cubans swiveled their hips effortlessly. Their fluid steps and graceful turns contrasted with the jerky and self-conscious movements of their partners.

“Jineteros” Deepa nodded her head toward the young men. “It literally means ‘jockey,’ but here in Cuba they use it to refer to street hustlers and sex workers.”

“But I thought that prostitution was illegal here.” I recalled reading that the revolutionary government had outlawed prostitution in 1961. Thousands of women who had been involved in the sex trade during the prerevolutionary era were introduced to other occupations through work-study programs and vocational schools.

“Well, nowadays most Cubans find it hard to make ends meet,” replied Deepa. “Prostitution is just another way to survive.” Next to me, a young white man in a Che t-shirt snuggled with a pretty Cubana with light brown skin and curly hair. Were they girlfriend and boyfriend? Was she a jinetera? How could you tell?

A half hour or so later, just as my lids were beginning to droop again, an announcement was made. The rap act Primera Base would be making an appearance. Sometimes rappers opened for the main acts at the rumba.

“Primera Base. Cool!” Deepa said in anticipation. “They’re one of Cuba’s most well-known rap groups, and they even have a disc out with EGREM.” EGREM was the state agency responsible for producing and marketing Cuban music. With scarce resources and a small local market for CD sales, EGREM had produced only a few rap CDs. They received little or no airplay on Cuban radio.

I strained my neck to get a good view of the stage. Three young men stood before the microphones. The one in the middle, Rubén Maning, had several thick gold chains around his neck. His shirt was open to reveal a bare torso. He wore plastic sunglasses studded with fake diamonds. Low-slung pants revealed a pair of white boxers with the letter X written in bold at the top. The other two also wore heavy gold chains and black sunglasses.

“It was like this,” opened Ruben, in a grave voice. He bowed his head dramatically. “The 21 of February 1965, he was shot up in the Audubon Ballroom About to give his last speech, before an auditorium of 400 blacks and half a dozen whites Yes! That gentleman you know as Malcolm X / WAS DEAD.” From the recorded background beat came the piercing tones of a siren, then people screaming and crying. The beat kicked in, and Rubén performed an homage to Malcolm X. “I want to be a black just like you, with your great virtue,” rapped Rubén, in an old-school flow. “I want to be a black just like you, a great leader, to be great.” The symbol of Malcolm was so powerful, I thought.

“Just like you, just like you, nigger,” Primera Base went on to rap in the chorus. “We wanna be a nigger like you / Just like you, just like you, nigger. A nigger like you.”

I sighed. Also powerful was the circulation of the N-word in a global marketplace. It made me wonder whether Cuban rappers were just a tropical version of white American kids in the suburbs, using black slang and getting their bling on. Were we just looking at the mirror image of a clichéd American commercial culture? And all this in a country that was supposed to be the last holdout against American global influence? Or maybe I was just looking in the wrong places.

Early hip hop culture in Cuba was generally produced and consumed in the local neighborhood. During this period of the late 1980s through the mid-1990s, people would play music from CDs brought from the United States. Rappers would rhyme in their houses, on street corners, and in local parks. When I arrived in Cuba in 1998, this local culture was still strong, even as hip hop was gaining ground in the clubs and venues like UNEAC. Randy Acosta was a rapper who began his career on the streets of his barrio, Almendares, a few miles from the center of the city. I went with Deepa to visit him and his mother, Lily. I thought that Randy might give me a sense of how Cuban hip hop looked from the streets. I figured we would take a taxi or a bus to get there. Deepa had other ideas.

“We’re hitchhiking,” she informed me once we were out on the street.

After the cult thriller The Hitcher, I thought no one hitchhiked anymore. In Havana not only did people hitchhike, but hitchhiking was enforced by the baton-wielding police. Few Cubans were privileged to own cars. Those who did were mostly people with a dollar income from tourism or

those who worked for a joint venture. Even then there was the gas shortage. The Soviet Union used to be Cuba’s main oil supplier, but in 1990 the Soviets just stopped delivering oil. Cuba’s transportation system was paralyzed. As the economy picked up slowly again, those with advantages were forced to share. Making sure that every car was full of passengers was one way of keeping things moving.

Deepa and I walked over to the intersection of Linea and Paseo to coger botella, as hitchhiking was known locally. Cubans refer to a ride as a botella, or bottle. So to coger botella was to get a ride. Deepa stuck out her thumb, true hitchhiker style. But when a red Volkswagen spluttered to a halt before us, the police officer directing traffic came over and bent down to speak to the driver. “Are you going to Playa?” he asked the driver, a thin older man in a pink shirt. “Yes,” was the response. “Then you can take them.” He motioned us toward the car. Legally enforced carpooling. Only in Cuba, I thought as we drove toward the tunnel to Miramar. In a revolutionary society solutions were collective and relied on people’s sense of obligation to others. And maybe some fear of the baton-wielding cops as well.

When we arrived at her house, Lily was watching her TV—a Russian model with a greenish hue to the screen. In the 1980s Lily had gone to Czechoslovakia to work with Cuban delegations. She spoke fluent Czech, another of those skills of little use in an era of Canadian and French joint ventures. She was a single mother who supported her son, Randy, on her peso salary from her job at an advertising agency.

As we chatted over thick Cuban coffee and mani, a popular sweet made from palm sugar and peanuts, Randy walked in. He pulled off his bicycle helmet and shot us a broad smile just like his mother’s. He tentatively pulled back a chair to sit down with us. As Randy talked about his passion for rap, he became more animated. He told us that he had always identified with rap, with its cadence and the drums. It was hard to find American music in Cuba. So he mostly watched bootleg recordings of video clips on friends’ VCRs.

His shyness dissipated, Randy performed his rap song “La Bicicleta” (The Bicycle). The song was about the scarcity of transportation and his journeys around the city on his Chinese-made Flying Pigeon bicycle. Randy’s five-year-old cousin Cesarito—who had memorized the words—repeated the lyrics and chimed in with a childlike attempted beatbox. As I looked on, it all seemed so familiar: the rhythms, the hand gestures, the flow. But what he was rapping about was entirely unfamiliar, a scene taken from the tableau of his own life and told in the vernacular of his peers.

The early gender politics of Cuban hip hop—like the race politics that I had witnessed with Primera Base—were still underdeveloped. As in most places around the world, the culture of machismo in Cuba was strong. As an ardent feminist, I was taken aback by the whistles and propositions that I, like most women, attracted from street-corner types. After years of organizing protest marches to mark International Women’s Day in Sydney, I was surprised to hear that on this day in Cuba women were handed roses and congratulated for being women. So would Cuban hip hop be any different? Deepa’s friend Pablo Herrera, Cuba’s most prominent hip hop producer, took us to a peña, a small afternoon rap show at the local Café Cantante. He said that we would see and meet some of the prominent women artists in Cuban hip hop.

Café Cantante was a small intimate venue facing the historic Plaza de la Revolución. We descended a series of marble stairs to the entrance, where we paid—yet again—five pesos each and then made our way into the club. Like most other venues struggling to survive the economic crisis, Café Cantante had to reorient itself toward a tourist market. Evening concerts that showcased top Cuban bands such as NG La Banda and Irakere cost upward of $25 per ticket, almost twice the monthly salary of a Cuban. The afternoons were when young Cubans had a chance to use the space, for rap or rock concerts.

“Respect! All crew, all massive, everywhere in the world You practice the art of hip hop This goes out to every boy and every girl.” Ariel Fernández, aka DJ Asho, was spinning, and the cramped space vibrated with the booming voice of KRS-One. At a table by the front of the crowded room sat a tall stick-thin guy and a reticent young black woman with springy brass-colored hair. Pablo introduced them as Alexey Rodríguez and Magia López, a husband-wife rap duo known as Obsesión.

“¿Voy a cantar?” I asked Magia in my beginner’s Spanish, misconjugating my verbs so that I was requesting to sing rather than asking if they would be singing, as I’d intended. “Si, un momento.” She conferred with someone at the back and then came back to announce that I had been added to the afternoon’s lineup. Oh, shit! I tried to explain the mix-up but to no avail.

On stage first was Instinto, the all-female trio extraordinaire. The women were dressed in low-cut and clingy outfits and high heels. As the salsa beat kicked in from the DJ booth, they gyrated their hips in a choreographed routine. The young men in the audience went wild. The divas onstage rapped in lyrical prose, spun on their heels, and sang in three-part harmony. This was the Cuban-streets-meet-high-brow-classical-training at Havana’s Instituto Superior de Arte. There was no way I could match a performance like this. Was it too late to get out of it?

Then the next act was being introduced, a Portuguese rapper from India. Heads, including my own, turned in anticipation of this exotic wonder until I realized they were talking about me. Too late. I smoothed down my blue jeans and hesitantly edged onto the stage. I had no slinky dress. I had no background beat. And, worst of all, I was performing solo. If there was an unspoken rule among Cuban rappers, it was that you always perform with one or more others—you never brave the stage alone. I could feel the collective gasp of shock as I came onto the stage—by myself.

I decided to sing one of my new pieces, “Woman Find.” The fast and scatlike rhymes were inspired by the jazz-hip hop fusion style of the LA-based rap group Freestyle Fellowship. I realized I would be totally incomprehensible to a Cuban audience. The song was a militant tract about women breaking beyond stereotypes and finding a voice in society. As I sang the chorus, “We’ll no more believe when they tell us we’re free,” Alexey and some others added improvised timbals with a spoon on the side of a glass. There were a few cheers and some scattered clapping when I finished. I figured that somehow, despite the language barriers, maybe the song had resonated among some people. As I walked down off the stage and back to my seat, I felt hands on my arm. “Que linda.” “Que guapa.” I was being surrounded by young men who liked my pretty song.

I sighed, deflated, and took my seat. “That was alright,” said Pablo, leaning over from his seat. “Maybe I can produce some music for you.”

Pablo lived in Santos Suárez, a formerly middle-class area in the southern part of the city now occupied by working-class blacks. It wasn’t until my next trip to Cuba, after spending a year and a half at grad school in Chicago, that I finally made it to Pablo’s place. I was curious about how rap music graduated from barrios like Almendares to the recording studios. If most of Cuba ran on old Soviet equipment, how did Cubans acquire the samplers and mixers and other expensive equipment required to make beats? A beat was the prerecorded background music that accompanied rappers as they performed. It had replaced the records played by DJs in early live rap performances.

I caught a cab to the modest two-story corner house that Pablo shared with his mother. There was a rich aroma of tomatoes. Pablo was cooking pasta. A sauce simmered on one burner, noodles on the other, and eggs boiled in another pan. After draining the noodles and dishing them into bowls with the sauce, he peeled the boiled eggs and crumbled them on top. Pablo saw the look on my face.

“I know, it’s weird,” he admitted, in his disarmingly impeccable English. “It’s just another habit from the Special Period. Cheese was so hard to come by, and we Cubans are always inventando, so we just substituted it with crumbled up eggs. Try it, it actually tastes pretty good!”

I sampled the local cuisine. The pasta sauce was tasty. I figured if I ever got caught in a special period, I’d just do witho

ut the cheese.

After we ate and cleaned up the dishes, we went into Pablo’s studio. It was a tiny room next to the kitchen. There was a Roland keyboard sampler, a Behringer mixing board, a microphone shielded by a homemade pop screen made of panty hose, a set of turntables, and—he showed me proudly—an Akai MPC digital sampler that had been sent by a US label that August. Pablo read the manual in English. In only ten days of working with the equipment, he had produced the first-ever Cuban hip hop album. It was called Cuban Hip Hop All-Stars, Vol. 1.

“We’re lucky to have equipment like this, because of our connections with record labels,” Pablo said, gesturing toward the sampler. “But we always have to make it clear that we reject the kind of consumerist ethic and materialism that drives hip hop as an industry. Like a few weeks ago, a photographer from Vibe magazine wanted to do a shoot of Cuban rappers wearing Tommy Hilfiger. We refused, because we knew that it was just an attempt by labels to get their products into Cuba.”

I nodded. Rappers were wary of being accused of “capitalist consumerism,” a desire for material goods that was at odds with being a revolutionary. Foreign labels—even underground ones—were capitalist corporations that tempted the rappers with record deals and expensive, hard-to-acquire equipment. Cuban rappers and foreign labels were engaged in a rumba guaguancó. They flirted with one another, each enticing the other while protecting themselves. The courtship worked only if both parties thought that they were using the other for their own ends.

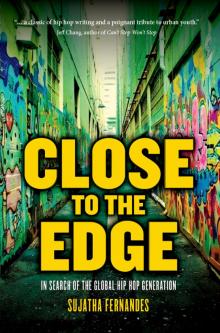

Close to the Edge

Close to the Edge